The Noise and the Signal

February 22, 2018

You’re driving down a highway on a cold and rainy night and you’re ravenous, so you take the next exit toward the familiar orange glow of your favorite fast food joint.

You’re driving down a highway on a cold and rainy night and you’re ravenous, so you take the next exit toward the familiar orange glow of your favorite fast food joint.

While exchanging credit for calories, a series of thoughts pass through your head: Where did this burger come from? How was it processed? Where do the ranchers who raised the beef live? And what is life like for workers and animals on these farms?

Then, like the headlights moving out of site across the interstate, your questions vanish out of view. It’s just too much to manage in one moment, and this large basket of fries won’t eat itself.

_____________________________

We live in an age when information has value, but only if we are able to consume these nuggets of input in meaningful, digestible ways. Knowledge about how we treat people, animals, and the environment can be a powerful force in the choices we make – but first we must be able to make sense of it.

The story of how AVP came to collaborate with the Gibbs Lab at the University of Wisconsin–Madison is one of learning about communities halfway across the globe. Holly Gibbs and her team have spent years gathering and interpreting data on Brazil, one of the world’s largest exporters of beef, chicken, and soy, to draw conclusions about impacts of increased agriculture there.

The story of how AVP came to collaborate with the Gibbs Lab at the University of Wisconsin–Madison is one of learning about communities halfway across the globe. Holly Gibbs and her team have spent years gathering and interpreting data on Brazil, one of the world’s largest exporters of beef, chicken, and soy, to draw conclusions about impacts of increased agriculture there.

Recently, the Gibbs lab uncovered additional statistics about the supply chain of ranchers, slaughterhouses, and rural farm owners in Brazil, so Gibbs asked AVP to help shed further light on the links between them.

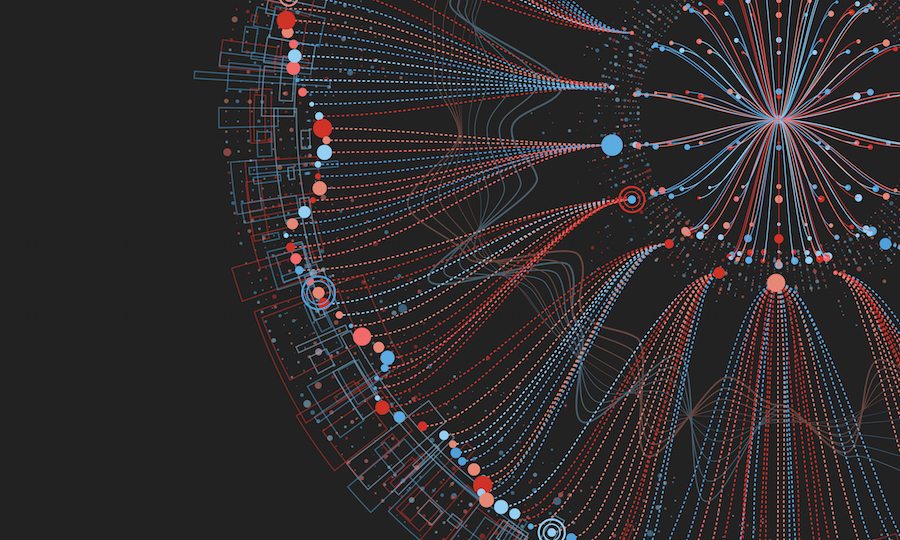

To do so, we imagined and built an environment so Gibbs’s team could integrate the datasets together, perform deep analysis, and answer unique questions about deforested properties and the supply chain, sales of meat to slaughterhouses, and how ranchers treat their workers and cattle.

In a time when anything, accurate or erroneous, can be called fake, transparency in the process is key to building trust. Chris Lacinak, AVP founder and president, says it this way: “If we say something, it better be right. And the only way to prove it is to show how we arrived at these statements in the first place.”

“To accomplish this, we documented everything and kept track of each step along the way to make the work transparent, repeatable, and authenticatable,” says Bert Lyons, AVP Senior Consultant and project lead.

AVP then went about designing a graphical user interface (GUI) to make the data accessible to a broader audience including potential retailers, grocery stores, and meatpacking companies.

“This way,” says Lyons, “environmental groups such as the National Wildlife Federation (NWF), which provided resources[1] to support this work, will be able to fully examine the results of Gibbs’s efforts and utilize this information to help advance conservation outcomes.” Government agencies, companies, academic partners, and stakeholders in Brazil will also be able to use deforestation, sales and other information in an open and transparent manner to help improve decision making processes in complex supply chains.

“In the past, many assumed it was impossible to link these disparate sources of information. Now we have shown that we can improve traceability in the cattle supply chains, which will allow for improved forest conservation,” says Gibbs.

And that’s what good data can do. It gives us a way to tune out the noise and get to the core of the issues to help advance real solutions. It also brings AVP closer to the research community, maximizing the skills of our team by both securing information and helping others interpret it in concrete ways.

And for Gibbs, joining forces with AVP is an opportunity to see their academic research come to life in new ways.

“Through our work with Bert and the AVP team, we were able to enhance the quality, innovation, and technical expertise of our science to build a novel database that documents cattle movements across much of the Brazilian Amazon’s agricultural frontier,” she says.

“There’s need for consistent approaches to archiving data that is not always possible within the typical rhythms of academic inquiry,” Gibbs adds. “AVP opened the door to new ways of accessing ‘big data’ for land change science, which is powerful especially when connected with our deep understanding of tropical deforestation and the Brazilian context.”

_____________________________

How much publicly available data is out there waiting to be acquired, analyzed, and reported? Voting habits of elected representatives? Links between drug resistance and hospital re-admittance rates? What about the relationship between energy policy and the climate?

How much publicly available data is out there waiting to be acquired, analyzed, and reported? Voting habits of elected representatives? Links between drug resistance and hospital re-admittance rates? What about the relationship between energy policy and the climate?

There are measurements for almost everything. And now AVP has a model to evaluate this knowledge so that universities, agency professionals, healthcare providers, political groups or anyone with an eye for observation can crunch the numbers, too.

Or, at the very least, they’ll be able to find out where the beef in their burger comes from.

[1] This work was funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation through the Collaboration for Forests and Agriculture, a joint effort of the National Wildlife Federation, The Nature Conservancy and World Wildlife Fund, to eliminate the loss and degradation of tropical and sub-tropical forest ecosystems that result from the production of globally traded agricultural commodities.